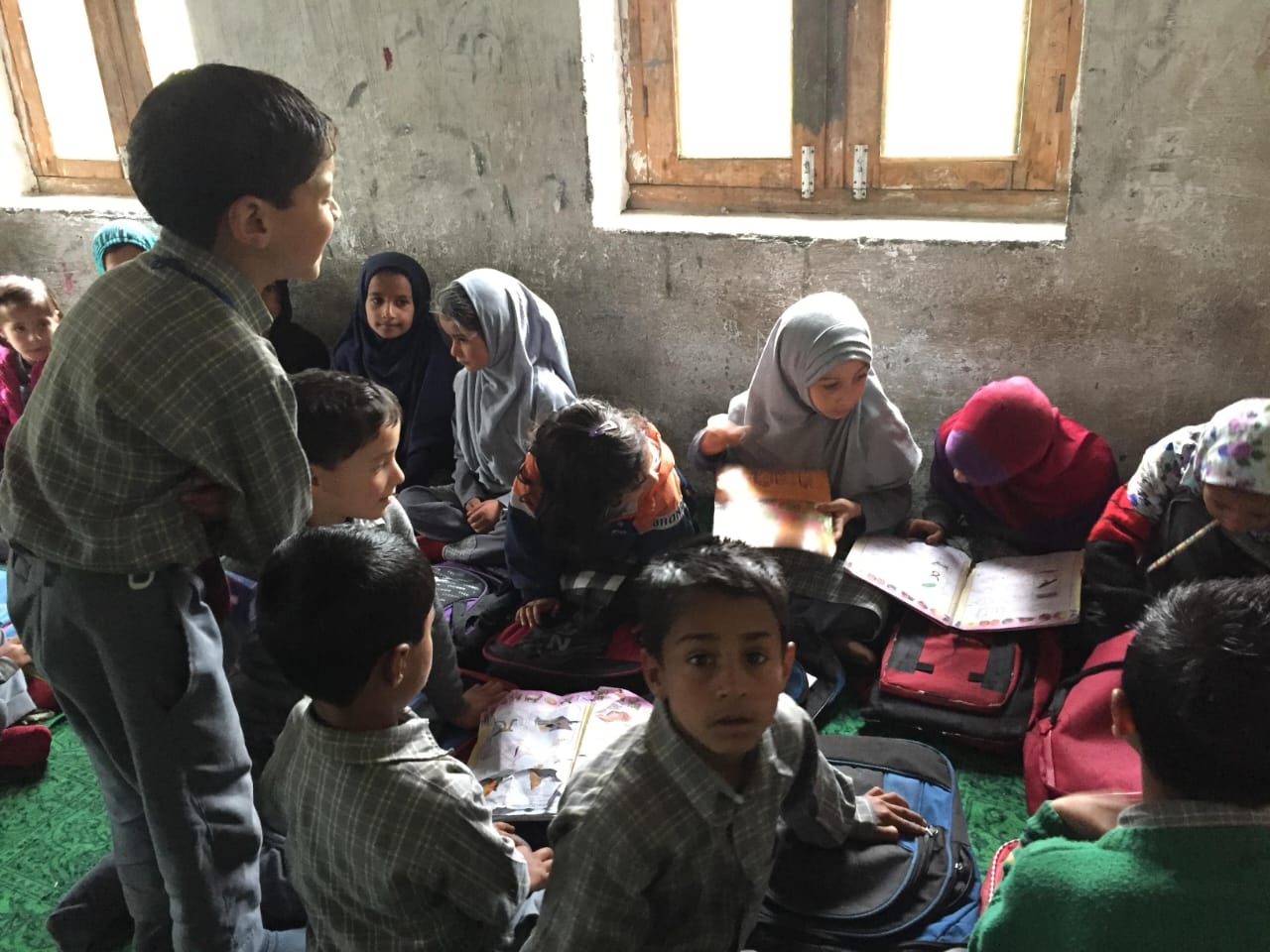

New Delhi, September 3: My senior editor once shared a touching story from a small village in Jammu and Kashmir. In that village, there was only one government school, and a single teacher was responsible for teaching all the subjects to every child. The entire fate of the school depended on the attendance of children living in the surrounding area. If many children stopped coming, the school could face closure.

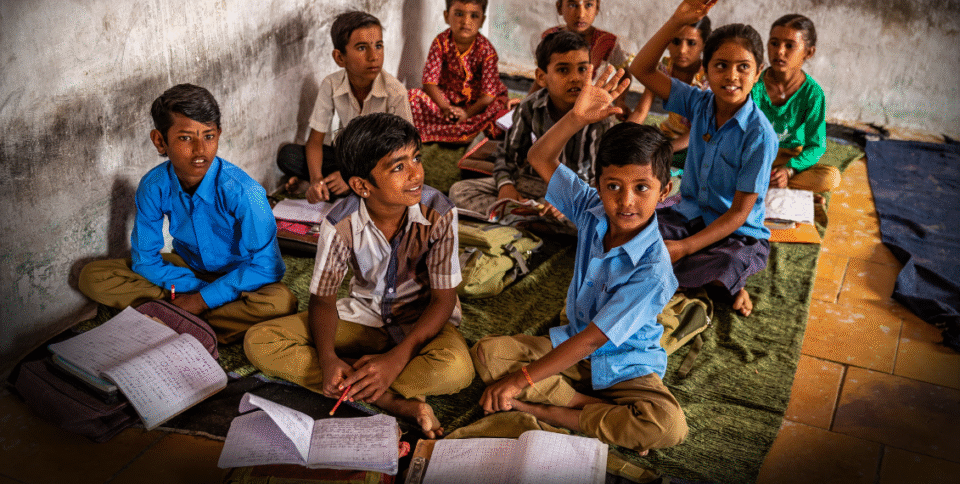

This story is not unique to J&K, it reflects a reality across rural India. In countless villages, small government schools stand as the only educational lifeline for children living miles away from urban centers. These schools are not just classrooms; they are spaces of hope, community, and opportunity. The closure of even one such school can mean the difference between a child staying in education or dropping out entirely.

Today, this issue has taken center stage in India’s most populous state, Uttar Pradesh, in North India, where the government is implementing a large-scale plan to merge thousands of small, under-enrolled schools into nearby larger ones. The goal, according to officials, is to improve educational quality, modernize infrastructure, and make better use of teachers and resources. Yet the decision has sparked protests, fears, and debates across the state. Parents, teachers, and activists are raising serious questions: Will children benefit from better facilities, or will longer travel distances push many out of school altogether?

Why Are Schools Being Merged in Uttar Pradesh?

With estimated population of 246.3 million people, Uttar Pradesh has nearly 1.37 lakh (137,000) government primary and upper primary schools. But a significant number of these schools, about 29,000 have fewer than 50 students each. These tiny schools often struggle with low attendance, limited resources, and lack of adequate teaching staff. For many years, officials have worried that maintaining so many under-enrolled schools results in inefficient use of funds and poor quality of education.

In June 2025, the UP government issued an order to “pair” or merge these small schools with better-equipped neighbouring schools. The main idea was to pool resources, improve infrastructure, and provide students with a more vibrant learning environment, consistent with the goals of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020. According to the government, merging these schools will allow for better teaching quality and access to facilities like smart classrooms and computer labs which small schools often lack.

Minister of State for Education Jayant Chaudhary explained that the mergers are “carefully mapped,” ensuring students will be relocated only to schools within a safe and feasible distance, and that closed school buildings would be repurposed to host pre-primary education centers called Balvatikas. The initiative aims to support foundational learning and early childhood care.

What Do the Data Say?

Between 2017 and 2024, the number of government schools in UP fell by nearly 16%, from 1,63,114 to 1,37,102. This decline is largely linked to the state’s recent mergers and closures. Despite this, dropout rates in UP have actually improved, showing a sharp decline over the past two years:

-

Dropout rates in middle school (classes 6-8) fell from 16% in 2022–23 to 3.9% in 2023–24.

-

Dropout rates in secondary schools (classes 9-12) dropped from 12.7% to 5.9%.

-

At the preparatory level (classes 3-5), dropouts declined from 20.2% to 5.4%.

These numbers are a positive sign and reflect efforts like mid-day meal schemes, better school facilities, and dedicated outreach programs.

However, the government’s decision to merge schools has faced strong resistance in many districts. Parents and teachers fear that longer distances to schools will discourage children, especially girls and those from marginalised communities, from attending regularly. Traveling further, often through unsafe routes, could lead to higher dropout rates, undoing progress achieved in the last few years.

Challenges Faced by Rural Children

For children in rural areas, nearby schools are often a lifeline. When schools are small, sometimes just a handful of children enroll, but the schools also serve as safe, accessible spaces where kids can learn close to home. Making students travel far away can be risky and expensive for families. Many children, especially girls, are expected by their families to stay closer to home rather than journey long distances daily.

Eight-year-old Amit from a village in Lucknow district summed it up simply: his walk to school used to be just 200 meters, but after the merger, he has to travel two kilometers. His father sometimes struggles to escort him on his bicycle because of his busy schedule. Such increased travel can become a serious hurdle to consistent schooling.

This concern is echoed by many parents and teachers, some of whom are worried that children might outright stop attending school rather than face the difficulties of traveling longer distances. Opposition leaders have also pointed out that most schools targeted for merging are in areas where electoral support for the government is lower, suggesting political motivations behind the closures.

Government’s Response and Plan Revisions

After protests and court challenges, the UP government revised its earlier merger policy. Now, schools with more than 50 students will not be merged, and no two merged schools would be more than one kilometer apart. Additionally, any schools separated by natural or man-made barriers like rivers, highways, or railway tracks are excluded from mergers.

The government has assured that no teaching jobs will be cut and that all teachers from merged schools will be placed in the receiving schools, improving teacher-to-student ratios and giving teachers better chances to specialize and teach effectively. Vacant school buildings will not fall to waste but will be repurposed as pre-primary centers or Anganwadis(govt. pre-school), aiding early childhood education efforts.

Basic Education Minister Sandeep Singh emphasized that the revised pairing initiative aims to improve educational quality, infrastructure, and safety for students. He also underlined that priority would be given to boosting facilities like smart classrooms, ICT labs, and extra rooms for schools with higher enrolment.

The merger policy has not only sparked protests but also legal challenges. Some petitions argue that merging and closing schools violates India’s Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, which mandates that primary schools be accessible within a reasonable distance.

Though the Allahabad High Court upheld the government’s school merger plan citing its alignment with NEP 2020 goals, the Supreme Court of India agreed to hear pleas against the policy to ensure children’s rights are protected.

Government officials argue that the plan aligns with sustainable education goals and is implemented with care to avoid affecting children’s access. However, courts continue to scrutinize the balance between resource optimization and the right to education.

The Bigger Picture Across India

While UP’s merger plan is currently in the spotlight, similar school rationalization processes have unfolded across many Indian states in recent years. Madhya Pradesh reorganized around 36,000 schools, Rajasthan merged 20,000 schools, and Odisha and Jharkhand also undertook school mergers to better use resources.

These efforts are in part responses to declining enrolment in small rural schools due to migration, urbanization, and demographic changes. The National Education Policy 2020 envisions clusters or complexes of schools sharing resources and infrastructure for better teaching standards and facilities.

However, nationwide, the closures and mergers have generated heated debates about equity, access, and community identity because the neighborhood school is often much more than a place to study.

The Digital Divide and Infrastructure Gaps

UP’s school infrastructure has seen improvements over 90% have toilets, electricity, and hand-washing facilities. However, access to technology remains limited. Only 40% of schools have computer facilities, less than 20% use mobile devices for teaching, and a mere 14.5% have smart classrooms with digital boards or smart TVs.

As schools merge, there is concern that children must travel farther for education, sometimes losing access to digital and modern learning environments unless infrastructure and technology investments increase rapidly.

Impact on Teachers and Staff

Teachers and their unions have raised concerns about the merger policy’s impact on employment, careers, and school leadership. Some smaller schools that operated with headmasters or senior teachers may now lose such positions, limiting opportunities for staff growth.

The government maintains that no teaching jobs will be lost and that all teachers assigned to closed schools will be transferred, but the uncertainty and changes have created unrest and protests among educators.

What Does This Mean for the Children and Communities?

The effect of merging or closing schools in rural India cannot be seen only through numbers or policies. It is about children’s lives, communities’ futures, and the fundamental right to education.

For children like Amit, who used to walk a short distance to school, the increase in travel can mean exhaustion, safety risks, and lost interest in studies. For parents, long distances raise fears about their children’s well being and add logistical challenges.

Neighborhood schools often serve as the social fabric for villages, providing a community space for learning and growth. Removing them risks weakening this social bond and may disproportionately impact girls, poor families, and marginalised communities.

The story my senior editor told about a single rural school teacher in J&K touches the heart of India’s educational challenges today. As the government of Uttar Pradesh navigates the complexities of merging thousands of schools, the stakes are high. Behind every policy and statistic lies the lived reality of millions of children hoping for a safe, welcoming place to learn.

The government’s intention is to improve education using better resources, but the path must protect children’s rights, local voices, and daily realities. As India moves toward modernisation and better learning environments, the question remains: How do we ensure that no child is left behind? How do we keep the promise of education alive, close to home, for every child in every village?

These questions are not just for policymakers; they are for every one of us who cares about the future of children and education in India.