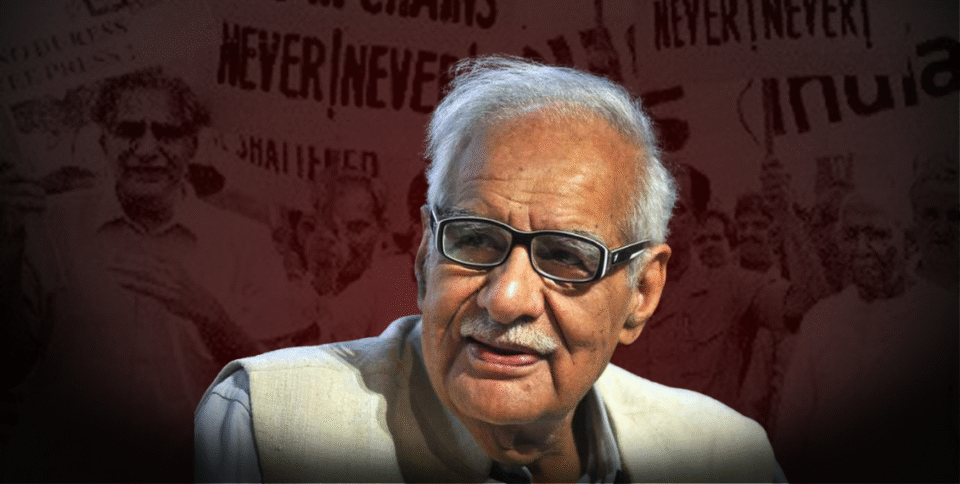

India, August 23: As India and Pakistan marked another Independence Day this month, both nations reflected on their shared histories and their diverging paths since 1947. Alongside freedom from colonial rule, one of the greatest promises of independence was freedom of expression – a promise still debated and fought over across South Asia. Press freedom in the region remains both vibrant and vulnerable: India’s democracy continues to wrestle with pressures on independent media, while Pakistan’s journalists often operate under risk and restraint. In this climate, the press is not merely a profession but the very backbone of democratic life. This is why the era of Kuldip Singh better known as Kuldip Nayar still feels so relevant. He stood for a fearless, principled journalism that spoke truth to power and refused to bow down to censorship. His life remains a reminder of what the press was meant to be, and what it still must strive to uphold.

Eminent columnist and author Kuldip Nayar was, in fact, a people’s man. Not only men of letters, but people from all walks of life loved and respected him. He was equally admired in urban and rural circles, which explains why his absence is so deeply felt today. A media world without Kuldip Nayar is undoubtedly poorer. His presence is missed not only in journalism but also in the democratic and human rights organizations where he lent his voice, including the People’s Union of Civil Liberties (PUCL), Citizens for Democracy (CFD), and People’s Union of Democratic Rights (PUDR).

Early Life

Born on 14 August 1923 in Sialkot (now in Pakistan) to Gurbaksh Singh and Puran Devi, Kuldip Nayar grew up at the crossroads of Sikh and Hindu traditions. His childhood home was close to the bungalow of celebrated Urdu poet Allama Iqbal, whom he often glimpsed with his close friend Shafquat. The poetry of Iqbal, especially Shikwa and Jawaab-e-Shikwa, left a deep impression on the young boy.

He also admired Abul Kalam Azad, leader of the Indian National Congress and later India’s first Education Minister, so much that he read Azad’s Persian masterpiece Ghubbare Khaatir seven times.

Though he qualified as a lawyer from Lahore Law College alongside Rajinder Sachar, Partition uprooted his life. Forced to migrate to Delhi as a refugee on 14 September 1947, he turned to journalism for survival. His first assignment was with the Urdu daily Anjaam, where he worked as Joint Editor for about a year. Destiny placed him at the Birla Mandir on 30 January 1948, where he covered the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi – his earliest, and perhaps most defining, moment as a journalist. Later, he joined another Urdu daily, Wahdat.

His shift from Urdu to English journalism carries an almost poetic irony. Hasrat Mohani, the poet and freedom fighter, advised him to leave Urdu journalism, convinced there was no future for it in post-Partition India. Mohani also discouraged Nayar’s own poetry, however heartfelt, believing the young man’s calling lay elsewhere.

Kuldip Nayar’s Rare Poetry

Before leaving poetry behind, Nayar wrote a memorable couplet, which Mohani, however, dismissed:

Unhen dekh kar hum ibaadat ko bhule

Jo dekha unhen to ibaadat bhi kar li

Khudai to bula lo qurb mein

Gunahon se hum ne to tauba bhi kar li

(I forgot my prayers after seeing her. Yet I said my prayers when I saw her. God, call me near You now, for I have vowed not to commit any sin.)

Heads English Media That Once Denied Him Entry

Nayar’s journey in English media began against resistance. After earning a Master’s degree in Journalism from Northwestern University’s Medill School, Chicago, he returned to India, only to face rejection from leading newspapers like The Times of India and The Hindu. Foreign-trained or not, they weren’t ready to welcome him.

Yet, persistence paid off. He began writing for Humayun Kabir’s feature agency, his first article titled To Every Thinking Refugee. Soon after, he joined the Press Information Bureau (PIB), which took him across India and eventually placed him alongside leaders like Govind Ballabh Pant, Lal Bahadur Shastri, and Jawaharlal Nehru.

By the late 1960s, he became General Manager-cum-Editor of United News of India (UNI), later heading The Statesman in New Delhi and the Indian Express group. In the early 1980s, his syndicated column Between the Lines appeared in 80 newspapers in 14 languages across India and abroad.

Nayar broke some of the most significant stories of his time. He was in Tashkent when Lal Bahadur Shastri died mysteriously after signing the Tashkent Declaration with Pakistan’s Ayub Khan. Against failing teleprinters and bitter cold, Nayar battled the odds to file the story ensuring The Statesman became the only newspaper to carry the news in its morning edition.

He also stood tall during India’s darkest hour, the Emergency of 1975. While many bent under censorship, Nayar resisted. His courage at the Press Club of India became legendary.

Courteous From the Core of His Heart

Despite his uncompromising principles, Nayar was courteous and humble. He bore criticism, even from his mentor Khushwant Singh, with grace. When Singh mocked him in his column With Malice Towards One and All, Nayar simply said: “Khushwant has been my teacher at Lahore College. How can I comment against him?”

When confronted with factual errors, he didn’t hesitate to accept mistakes. In 1987, after being challenged on a claim in Between the Lines, he readily agreed and asked for a corrigendum to be published.

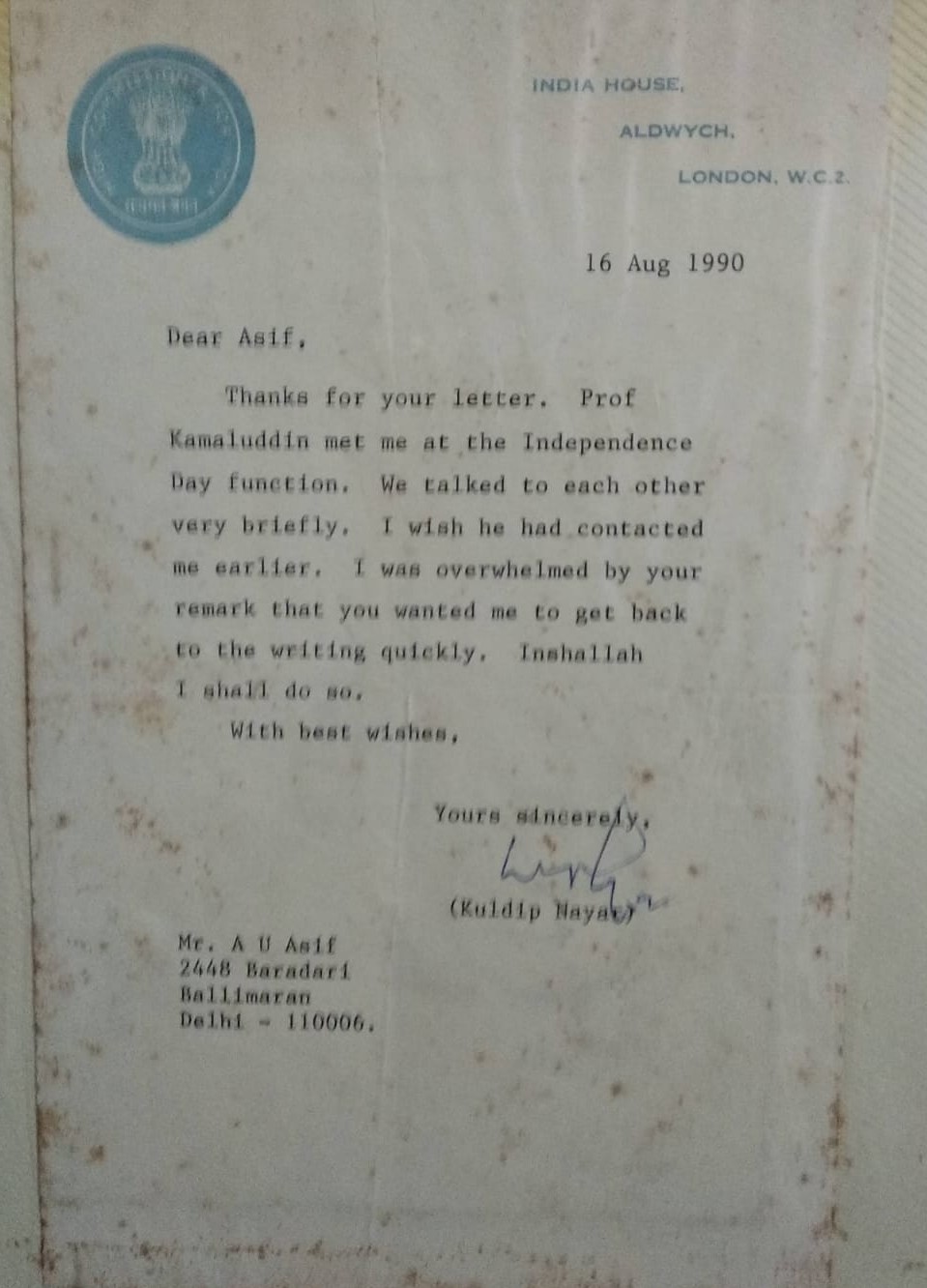

Even in diplomacy, as India’s High Commissioner to the UK, he retained the heart of a journalist. In a letter dated 16 August 1990, replying to a suggestion that he return to journalism, he wrote warmly: “I was overwhelmed by your remark that you wanted me to get back to writing quickly. Insha’Allah, I shall do so.” True to his word, he returned within weeks and resumed his columns.

A People’s Man: Unforgettable Events at Darbhanga

Nayar’s popularity reached far beyond Delhi. In 1993, during a visit to Darbhanga in Bihar, he was received like royalty. Invited by communities across religious and social lines like schools, madrasas, libraries, churches, gurudwaras, he embodied the respect journalism once commanded in India.

At one such moment, a child, watching his grand arrival, asked innocently: “Raja aa raha hai?” (Is a king coming?). In a way, she was right. He was an uncrowned king of Indian media, whose pen inspired reverence across divides.

His warmth touched people everywhere. Whether it was a bureaucrat longing for his company or a businessman ashamed after insulting him, those who met Nayar never forgot the encounter. His influence went beyond the printed word – it was deeply human.

His Legacy

The life of Kuldip Nayar is not just a story of one man’s rise. It is the story of modern Indian journalism, its resilience, its battles, its duty to speak truth to power. From the pages of Urdu dailies to the corridors of international diplomacy, from being denied entry into English media to heading it, his journey remains one of conviction.

- At a time when India and Pakistan, even while celebrating their independence, continue to grapple with the meaning of true freedom, remembering Kuldip Nayar is crucial. His era reminds us that independence is hollow without a free press. A world without him may feel poorer, but his values – courage, fairness, humility, and service to the people remain a guiding light.

His magic was his pen, and his pen belonged to the people.