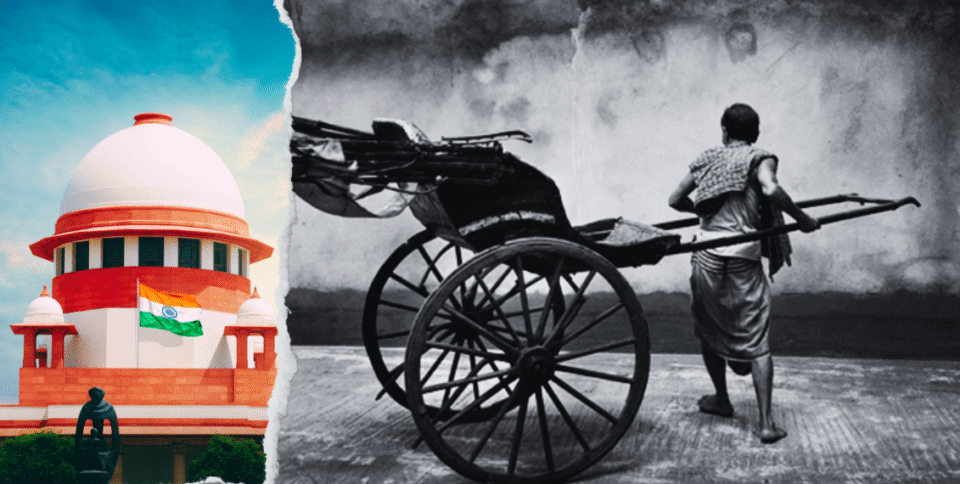

New Delhi, August 21: In 1953, the black-and-white classic Do Bigha Zameen etched an unforgettable image into Indian cinema: Balraj Sahni as Shambhu, once a proud farmer, reduced to pulling a hand-pulled rickshaw through Kolkata’s unforgiving streets. His cracked feet slapped against the asphalt; his chest heaved as the wooden shafts pressed into his shoulders. More than a mode of transport, the scene exposed a deep humiliation: a man being forced to haul another for survival.

Seven decades later, this indignity is not confined to celluloid memory. It has lived on in South Asia’s bylanes and hill stations, where men continued to pull men in the name of livelihood. In July this year, India’s Supreme Court finally struck a decisive blow by banning hand-pulled rickshaws in the ecologically fragile town of Matheran, near Mumbai—calling the practice “against the basic concept of human dignity.”

A bench led by Chief Justice B.R. Gavai reminded the nation that those engaged in such work are rarely there by choice but by compulsion, aligning the practice with forced labour under Article 23 of the Indian Constitution.

A Colonial Inheritance That Refuses to Fade

Hand-pulled rickshaws arrived in India in the late 19th century, imported from Japan by British colonialists. What began as a novelty for transporting the elite through narrow, congested streets soon became a brutal symbol of hierarchy: one human body yoked to the service of another.

Migrants from impoverished districts filled the ranks of rickshaw pullers. Their only asset was their physical endurance. Even after independence in 1947, the practice survived—an uncomfortable reminder that colonial legacies can outlast empires.

South Asia is replete with such vestiges. From bonded labour in brick kilns of Pakistan and Nepal, to indentured-style domestic work in Bangladesh, to caste-linked manual scavenging in India, the region continues to carry the weight of structures entrenched by colonial economics and social ordering.

Why the Ban Matters Beyond Matheran

The Matheran judgment is not only a matter of local transport policy; it is a symbolic rupture with a practice that degraded human dignity for over a century. In a region where the colonial “Raj mentality” often still seeps into governance and labour systems, such rulings signal a slow but necessary dismantling of inherited inequalities.

South Asia’s modern states often claim progress, but the persistence of such practices points to a deeper failure of social reform. Poverty, weak labour protections, and entrenched hierarchies ensure that even postcolonial nations continue to perpetuate colonial-style exploitation—sometimes under new garbs.

Toward Dignity and Justice

The Supreme Court’s intervention offers a reminder: breaking free from colonial chains is not merely about sovereignty or flags but about restoring dignity in daily life. South Asian societies must ask why, 78 years after independence, men still pull men, women still clean dry latrines, and children still toil in debt-bonded fields.

During the hearing, the Supreme Court delivered scathing criticism of the ongoing use of human-pulled carts, stating it runs counter to “the basic tenets of human dignity and constitutional morality.”

Chief Justice Gavai remarked, “Seven decades after independence, it is deeply regrettable that such an inhuman practice still persists.”

Ending such practices requires more than court orders. It demands political will, economic alternatives, and a moral commitment to ensure that development is not built on degrading labour.

The hand-pulled rickshaw’s final disappearance from Matheran’s slopes may seem like a small step. But symbolically, it is a stride toward a South Asia that not only remembers colonialism but also consciously refuses to replicate it.

How the World Moved Beyond Colonial-Era Labour Exploitation

Japan: Ending Human Rickshaws

Ironically, rickshaws were invented in Japan in the 1860s. By the early 20th century, Japan began phasing them out as motor transport expanded.

But importantly, rickshaw pullers weren’t left stranded. Many were absorbed into the growing public transport sector—becoming tram conductors, drivers, and mechanics—as industrialisation created new jobs. By the 1950s, human rickshaws had become tourist curiosities, not survival tools.

China: The Transition from Rickshaw to Cycle Rickshaw and Beyond

China, once home to tens of thousands of pullers in Shanghai and Beijing, outlawed hand-pulled rickshaws after the Communist Revolution in 1949.

The state organised pullers into cooperatives, provided training, and introduced cycle rickshaws as a less degrading alternative. Over time, they were absorbed into state-run transport services or factory work, aligning dignity with livelihood.